I am a novice at this though I’m older than some of those towering cottonwoods along the waterways. They have the advantage of growing at a rate of several feet a year while I am now shrinking, though at a much slower pace.

Nevertheless, I’m going to venture to say some things about the trees and places I’ve come to care about as I try to make up for a dreamy childhood. That was a time in which the things growing around me existed more as symbols of my inner states than as living things to be observed closely and to be understood as living beings in the world as I was.

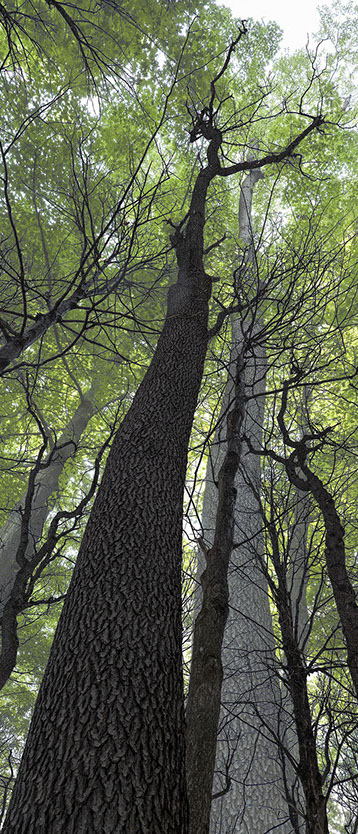

One of the first trees I fixed upon was this elegant towering black cherry, though I have to admit I didn’t know what it was at first. I photographed it over a year and a half and here I show you the same tree, skeletal in winter and surrounded by the winter skeletons of maple. This is juxtaposed over those same trees in summer where all the maples are in leaf but only the crown of the black cherry thrusting above them is foliated. When it’s surrounded like this it has to invest its energy in keeping above the crowd rather than bushing out,

because it isn’t very shade tolerant while the trees around it are. So if you see one in an open field that was probably formerly cropland you’ll see a much different looking tree. You probably won’t see it around former pastures because it is poisonous to cattle. But not to deer, which sometimes eat the shoots of its progeny.

We are lucky to have a lot of these trees growing in accessible Reinstein Woods which combines parklike paths with the practice of keeping interference to a minimum so you can easily see forests where, for instance, fallen trees are left in place to decompose over the years. In doing this they are furnishing nitrogen and other nutrients for new trees to grow and meanwhile playing host and breadbasket to a myriad of moss, fungus, insects and small mammals which aid in that breakdown and are also necessary to a functioning, healthy ecosystem. Possibly the primary hindrance to balance is the overpopulation of deer who devastate the undergrowth of its variety, freed from any natural predators (including us in this case).

The biggest concentration of cherries is on the south side of Flattail Lake. (Beware: the otherwise very well done color map available at the entry has South on top.) They start near the Stone House and are numerous up to the Beech path. The first part of this was already designated black cherry-ash-red maple forest by Bruce Kershner in his invaluable book “Buffalo’s Backyard Wilderness”** published in 1993. The second part of the cherry dominant area that continues on to Beech Path Kershner at that time designated Mature Sugar Maple-Beech forest. The Sugar Maples are still there along with some of the beech. One of the things that has thrown a wrench into Kershner’s predictions about what the climax forest would look like is the inundation, due to globalization, of American forests by predators that our native plants are unprepared to defend against. Nor could he have overseen the devastation that climate change is visiting on our forests. So the Beech bark disease is a kind of one-two punch from: 1) the Beech scale insect, European in origin, introduced in Canada in the 1890s and 2) from a fungus which is native to the U.S. The insects open up the bark and the fungus enters where it infects the growing and nutrient transporting layers and often eventually kills the tree. Whether this has happened here I can't at this time verify.

In any case, the dominant crown tree in the area as we continue along the south side of the lake towards the Beech Path is now the Black Cherry among sugar Maple. Some ash and some beech are still there and we will feature them in a future entry.

View along this path on the south side of Flattail Lake nearthe Stone House

***WNY Heritage, where I got my copy of Kershner's book

a year ago, may still have some available.

I am working on a list of books I have found most valuable for a future entry.